Taxonomie

Due to the element nature, Lanthanotus has become increasingly subject of biological science and has a turbulent taxonomic history.

Steindachner assigned the lizard to an own family, the Lanthanotidae (Steindachner, F., 1877) on account of the unique characteristics in the world of the lizards.

Some 20 years after this first classification, the Belgium herpetologist Georg Albert Boulenger assigned Lanthanotus to the beaded lizards (Helodermatidae) domiciled in America. Based on a few similar characteristics (body shape, forked tongue) he believed to ascertain a genetic relationship between the earless monitor lizard and the beaded lizards (McDowell, Jr., S.B. & Bogert, C.M., 1954). Not until 1954, did this taxonomic classification change again. Mac Dowell and Bogert, who conducted scientific research on American Gila monsters and their relatives from Central America and Mexico, abandoned the apparent similarity of Lanthanotus with the Helodermatidae as coincidental (evolutionary convergence) and henceforth classified the earless monitor lizard taxonomically between the beaded lizards and the monitor lizards (Varanoidae) (McDowell, Jr., S.B. & Bogert, C.M., 1954).

However, the real taxonomic innovation was the fact that Lanthanotus was henceforth classified as snake-like due to their similarity to snakes.

Yet, even this categorization has never been explicit and was fundamentally torn over time by two incidents; on the one hand by a groundbreaking change in the scientific classification methodology.

Phylogenetic systematics, founded by the German biologist Willi Hennig, is neither based on similarities nor on typical characteristics but rather exclusively on the genealogical relationship resulting from a chronological relational bifurcation of the phylogeny. Two species are even more near relatives the shorter the previous common ancestor dates back. In contrast to the typological (characteristic-based) taxonomy, phylogenetic systematics are subject to an objective basis, the historic process of phylogeny. Therefore, fossil findings could be the key to systematic classification (Richter, S., 2013).

Lanthanotus have serpentine characteristics (e.g. small eyes, forked tongue, and long body). Yet, these characteristics may also be found relating to other lizards (Rippel, O., 1983).

The thesis of the earless monitors’ close relationship to snakes was completely shaken by approximately 75-million-year-old fossil finds in the Gobi Desert. The Polish palaeontologist Magdalena Borsuk-Bialynika found fossil remains of a lizard there that she named Cherminotus, and appeared to be morphologically almost identical to Lanthanotus apart from smaller differences (Borsuk-Bialynika, M., 1984). This classification is however not without controversy among paleo herpetologists (verbal announcement Smith, K.).

As far as the systematic classification of earless monitor lizards is concerned, this meant at any rate: ‘back to go’ or ‘back to the roots’.

In the same way as Steindachner - the currently prevailing doctrine classifies the earless monitor lizard as an own family with a closer systematic connection to the family of the monitor- and beaded lizards. Besides ‘dry’ theory and at this stage, it should already be pointed to observations of ritual fighting among male earless monitor lizards that have striking resemblance to respective ritual fights between male monitor- and beaded lizards.

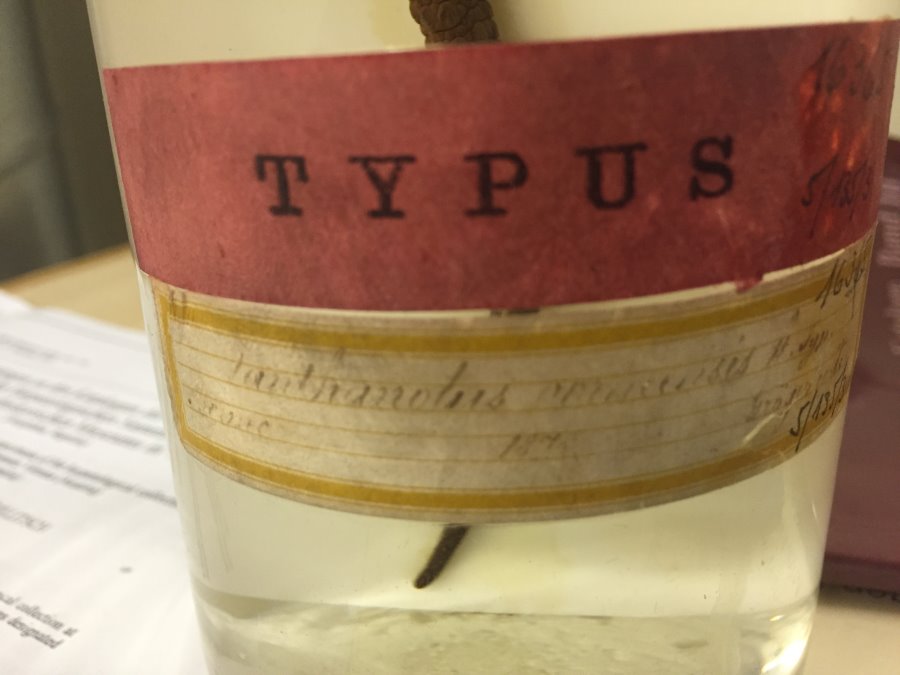

Holotype Lanthanotus borneensis, Natural History Museum Vienna